Stay up to date with free updates

Simply sign up to Oil and gas industry myFT Digest — delivered straight to your inbox.

The writer is a senior fellow and director of the Africa program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Angola’s dramatic exit from the OPEC+ oil cartel late last year has been interpreted as a historic pivot to the west. The less understood but equally important factor in his departure was the divergent impact of oil production shares between African countries and their counterparts in the Middle East, Asia and Russia.

Despite the fact that oil prices are high from 2021, most African oil producers are not experiencing a boom. In the short term, this affects their tax positions. In the long term, it will reduce their access to the financial resources needed to undertake development projects and the transition to low-emission economies.

The price of oil reached an average price of $82 per barrel in 2023, well above the $65-70 benchmark set by most governments. However, the 10 oil-rich African countries that have been exporters since at least 2000 have smaller trade surpluses than they did in 2010, when oil was $79 a barrel. They also have heavier debt burdens – on average around 85% of GDP. Meanwhile, many of their non-OPEC+ peers have larger trade surpluses and lower debt-to-GDP ratios.

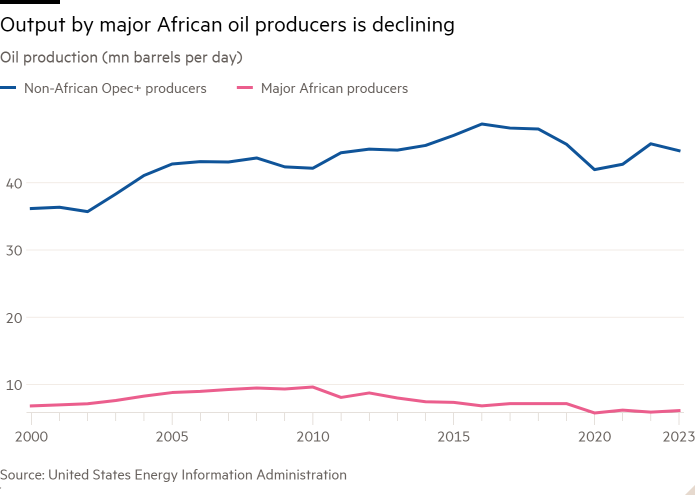

On the supply side of this widening divergence, output among major African oil-producing countries is falling. Countries including Congo-Brazzaville, Angola and Equatorial Guinea have seen significant contractions in oil production. Nigeria experienced the most dramatic decline, falling from about 2.5 million barrels of crude oil per day in 2010 to 1.5 million b/d in 2023.

In contrast, production among non-African OPEC+ countries such as Saudi Arabia, Oman, Russia and Kazakhstan increased. Even conflict-torn Iraq nearly doubled its oil production over the same period.

This decline in Africa can be attributed to years of underinvestment. This is due to outdated legislation, strained relations with communities involved in onshore production and even the favorability of alternative jurisdictions in Africa and elsewhere such as Guyana, now the world’s fastest growing economy.

On the demand side of the equation, the destination of African crude has also changed.

The shale revolution propelled the US to the status of the world’s largest oil producer in 2018, dramatically reducing its imports of African crude. The value of Chinese oil imports from major African oil producers also fell by about 28% between 2018 and 2023. This contraction is particularly sharp for Algeria, Angola, South Sudan and Libya, which previously relied heavily on measure in the Chinese market. Meanwhile, Chinese oil imports from non-African OPEC+ countries, including Russia, rose 78%.

Europe, still a significant importer of African crude, is expected to drastically reduce its oil consumption over the next decade as part of plans to rapidly decarbonise. Meanwhile, India is sourcing cut-price oil from Russian producers who are locked out of European markets.

Declining African oil production matters to the world. Despite high global prices, African governments, with insufficient oil export revenues, find it extremely difficult to balance their budgets.

Some climate activists may celebrate Africa’s declining oil production. But it will have a negative effect on the ability of these countries to mobilize the necessary financing for long-term energy transitions. The African continent already faces an annual financing gap of $400 billion a year by 2030 if it is to meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, according to the African Development Bank.

An important source of finance for Africa’s climate and development should be the recycling of petrodollars for investment in green sectors such as climate-smart agriculture and renewable energy. This is the playbook of Gulf Arab monarchies and Norwegian politicians, both of whom use oil revenues through major sovereign wealth funds in the green industries of the future. If Africa’s richer oil-producing countries are unable to finance their energy transition, the poorer ones will struggle even more.

To reduce global warming, the world must eventually reduce the production and consumption of fossil fuels. This will be a painful process for countries everywhere. But the energy transition could be even more problematic for African nations that are unable to capture and reinvest revenues from their natural resources. In an era of declining support among Western taxpayers for government provision of foreign aid to distant lands, we should pay more attention to the inability of African petrostates to finance their own development.

#Africas #petrostates #missing #oil #boom #matters